Frequently Asked Qestions

What is ‘”missing middle” housing?

The scale of middle housing is defined as the range of building typologies that are of higher density than houses and lower density than large mid-rise or high-rise apartment buildings.

The scale of middle housing is defined as the range of building typologies that are of higher density than houses and lower density than large mid-rise or high-rise apartment buildings.

What is a

single exit stair (SES) building design, also known as a point access block (PAB)?

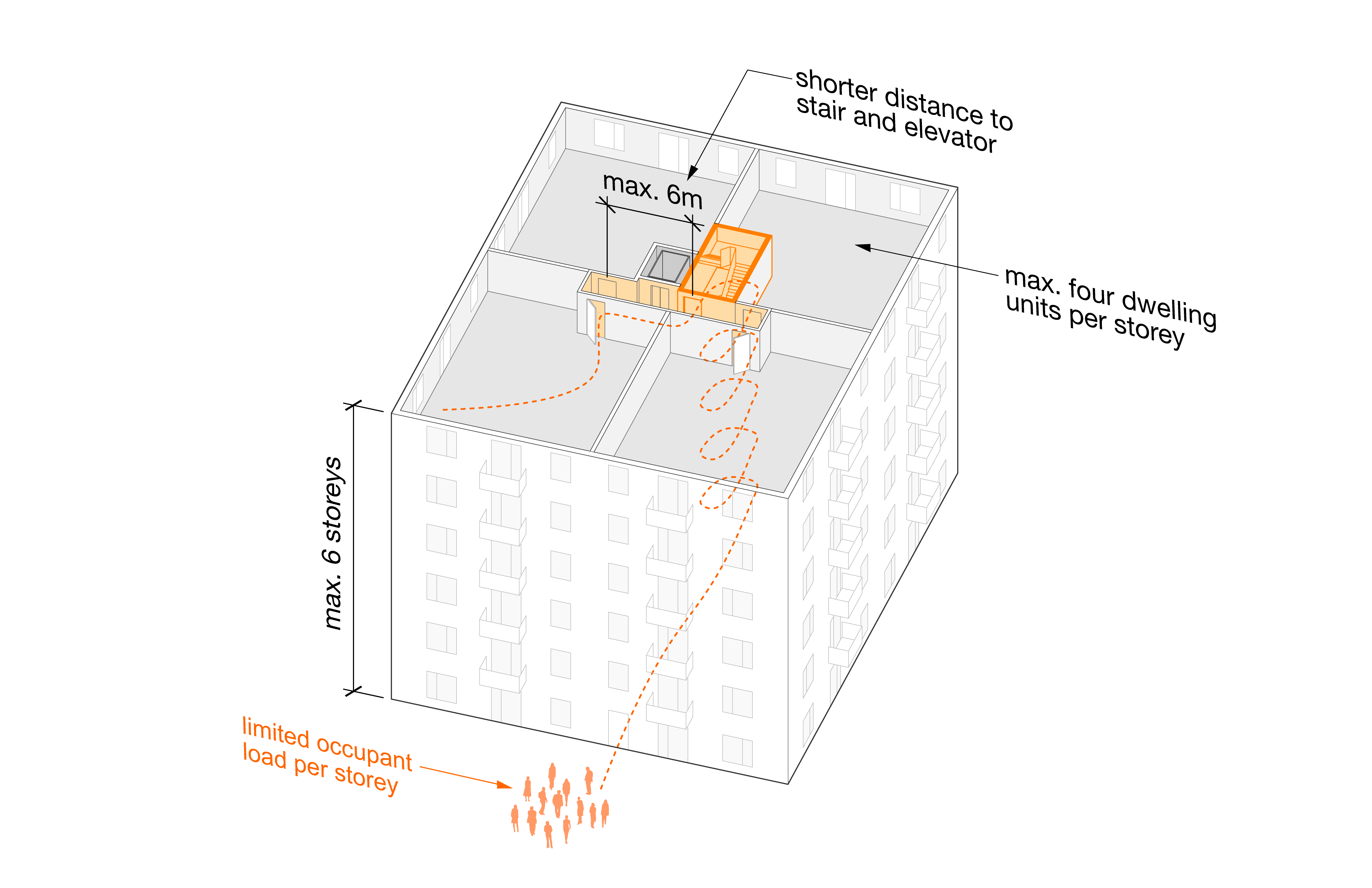

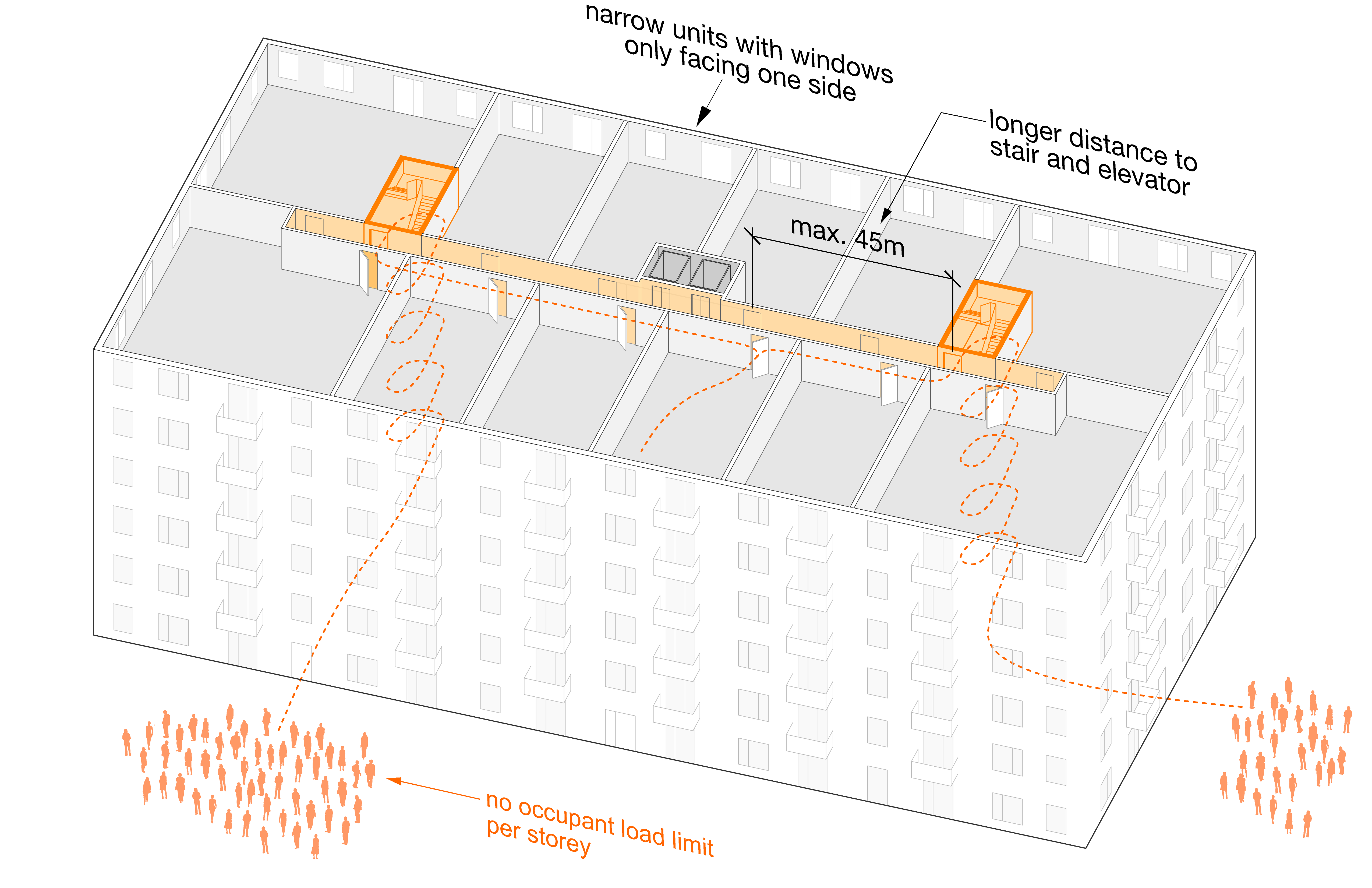

For the purposes of this project, single exit stair building design refers to small multi-unit residential buildings of 3 to 6 storeys in height with no more than four dwelling units per storey served by a single exit stair, and having a maximum travel distance from each dwelling unit entry door to the exit of not more than 6 metres.

![]()

![]()

Comparison between 6-Storey Single Exit Stair (SES) and Typical Apartment Building Design

For the purposes of this project, single exit stair building design refers to small multi-unit residential buildings of 3 to 6 storeys in height with no more than four dwelling units per storey served by a single exit stair, and having a maximum travel distance from each dwelling unit entry door to the exit of not more than 6 metres.

Comparison between 6-Storey Single Exit Stair (SES) and Typical Apartment Building Design

How can this solution remove barriers to the creation of new housing, or the preservation of existing housing units?

Single exit stair building design improves the feasibility of middle housing both as new supply and as additions/renovations to existing buildings. For instance, the solution allows a three-storey house to be reconfigured as a triplex, benefiting the creation of new supply and preservation of existing housing.

Architects generally consider a ‘double-loaded corridor’ to be the most efficient apartment building layout, yielding around 85% floor area efficiency. This metric is important to decide whether a project is financially feasible. However, it can be very difficult to achieve this efficiency on smaller sites such that they remain undeveloped until adjacent ones can be assembled to create sufficient economies of scale. For a small apartment building on a narrow lot, this solution increases the floor area efficiency by 5-15% or at least one extra bedroom per storey.

Single exit stair building design improves the feasibility of middle housing both as new supply and as additions/renovations to existing buildings. For instance, the solution allows a three-storey house to be reconfigured as a triplex, benefiting the creation of new supply and preservation of existing housing.

Architects generally consider a ‘double-loaded corridor’ to be the most efficient apartment building layout, yielding around 85% floor area efficiency. This metric is important to decide whether a project is financially feasible. However, it can be very difficult to achieve this efficiency on smaller sites such that they remain undeveloped until adjacent ones can be assembled to create sufficient economies of scale. For a small apartment building on a narrow lot, this solution increases the floor area efficiency by 5-15% or at least one extra bedroom per storey.

How can this solution increase the safety, accessibility and feasibility of small multi-unit residential buildings?

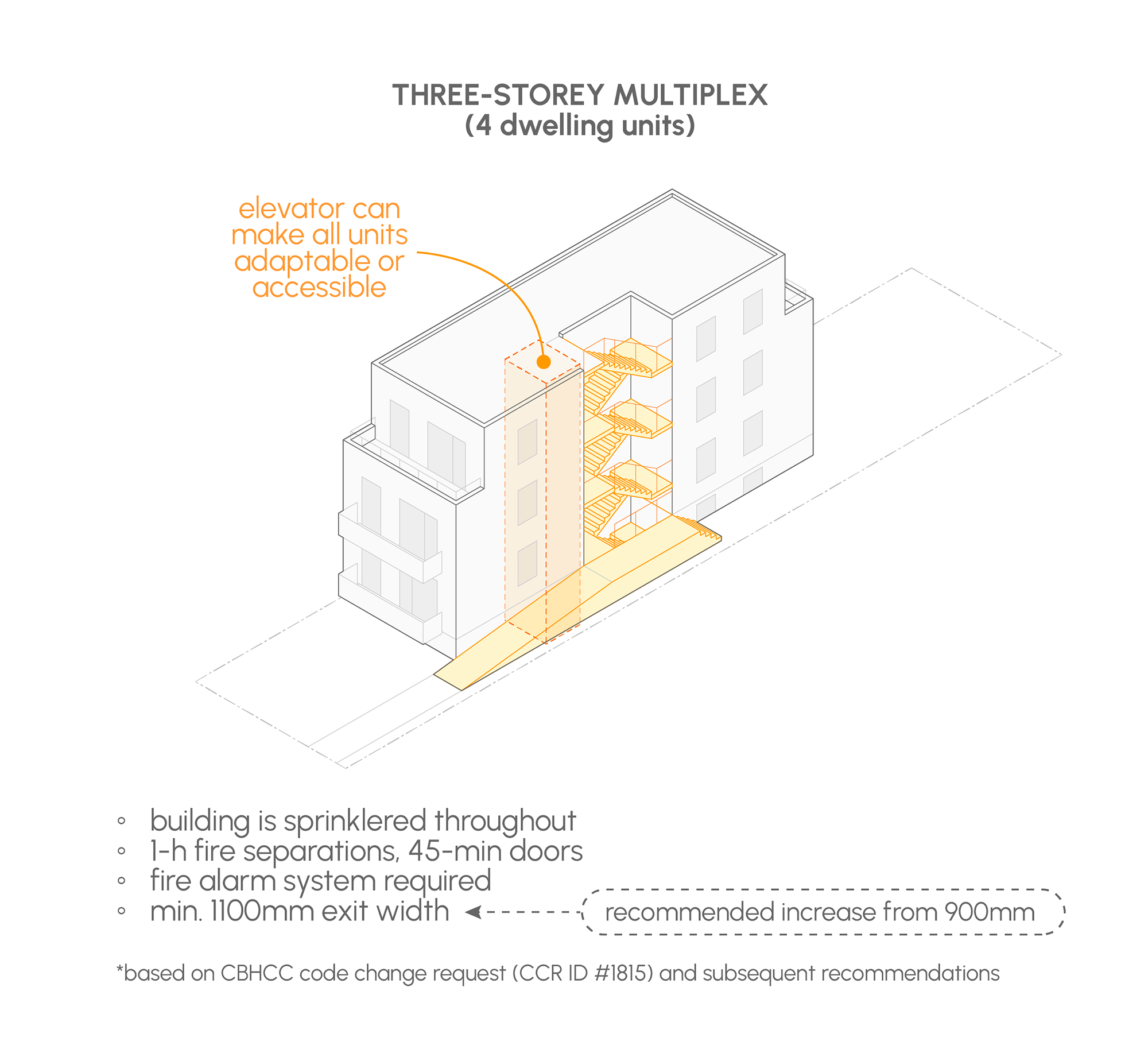

LGA Architectural Partners recently collaborated with the University of Toronto on a research project titled ReHousing (please visit www.rehousing.ca). We studied how much housing can be added to existing neighbourhoods if four to six dwelling units are permitted on any residential lot and identified two main types of layouts: stacked townhouses, where each unit has an internal staircase and separate entrance; and multiplexes, where several units are accessed from a common entrance. The 1980 edition of the National Building Code of Canada introduced permissions for stacked townhouses to be served by a single staircase whereas multiplexes are required to have two means of egress.

Single exit stair building design makes multiplexes more competitive with stacked townhouse layouts by increasing the floor area efficiency of the building. The design flexibility of a shared building entrance and single exit stair also makes it easier to provide an elevator to make all of the units barrier-free accessible. This design flexibility also accomodates stacking of structural, mechanical and plumbing systems.

![]()

![]() Comparison between

3-Storey

Multiplex and Typical

Stacked Townhouse Building Design

Comparison between

3-Storey

Multiplex and Typical

Stacked Townhouse Building Design

LGA Architectural Partners recently collaborated with the University of Toronto on a research project titled ReHousing (please visit www.rehousing.ca). We studied how much housing can be added to existing neighbourhoods if four to six dwelling units are permitted on any residential lot and identified two main types of layouts: stacked townhouses, where each unit has an internal staircase and separate entrance; and multiplexes, where several units are accessed from a common entrance. The 1980 edition of the National Building Code of Canada introduced permissions for stacked townhouses to be served by a single staircase whereas multiplexes are required to have two means of egress.

Single exit stair building design makes multiplexes more competitive with stacked townhouse layouts by increasing the floor area efficiency of the building. The design flexibility of a shared building entrance and single exit stair also makes it easier to provide an elevator to make all of the units barrier-free accessible. This design flexibility also accomodates stacking of structural, mechanical and plumbing systems.

Comparison between

3-Storey

Multiplex and Typical

Stacked Townhouse Building Design

Comparison between

3-Storey

Multiplex and Typical

Stacked Townhouse Building DesignNational Building Code of Canada

The following questions and anwers are provided for information purposes only and include many direct excerpts from the 2020 National Building Code of Canada, the 2015 NBC Part 9 Illustrated User’s Guide and the 1995 NBC Part 3 Illustrated User’s Guide.

What is an objective-based code?

From the CCBFC Archive:

“An objective-based Code includes objectives or goals that the Code is meant to achieve. In an objective-based Code, every technical requirement achieves one or more of that Code's stated objectives (e.g. Safety, Health, Accessibility, Fire and Structural Protection of Buildings, Environment). Applying the provisions in the Codes is one option for compliance, since they meet one or more of the Code's stated objectives by default. The other option is the use of alternative solutions. These must achieve at least the same level of performance and satisfy the same objective(s) assigned to the associated Code provisions.”

From Page viii of the 2020 National Building Code of Canada:

“The NBC's objectives are fully defined in Section 2.2.of Division A.

The objectives describe, in broad terms, the overall goals that the NBC's requirements are intended to achieve. They serve to define the boundaries of the subject areas the Code addresses. However, the Code does not address all the issues that might be considered to fall within those boundaries.

The objectives describe undesirable situations and their consequences, which the Code aims to prevent from occurring in buildings. The wording of most of the definitions of the objectives includes two key phrases: “limit the probability” and “unacceptable risk.” The phrase “limit the probability” is used to acknowledge that the NBC cannot entirely prevent those undesirable situations from happening. The phrase “unacceptable risk” acknowledges that the NBC cannot eliminate all risk: the “acceptable risk” is the risk remaining once compliance with the Code has been achieved.

The objectives are entirely qualitative and are not intended to be used on their own in the design and approval processes.

The objectives attributed to the requirements or portions of requirements in Division B are listed in a table following the provisions in each Part of Division B.”

What is an alternative solution?

From the Notes to Part 1 Compliance of the 2020 National Building Code of Canada:

“A-1.2.1.1.(1)(b) Code Compliance via Alternative Solutions. Where a design differs from the acceptable solutions in Division B, then it should be treated as an “alternative solution.” A proponent of an alternative solution must demonstrate that the alternative solution addresses the same issues as the applicable acceptable solutions in Division B and their attributed objectives and functional statements. However, because the objectives and functional statements are entirely qualitative, demonstrating compliance with them in isolation is not possible. Therefore, Clause 1.2.1.1.(1)(b) identifies the principle that Division B establishes the quantitative performance targets that alternative solutions must meet. In many cases, these targets are not defined very precisely by the acceptable solutions—certainly far less precisely than would be the case with a true performance code, which would have quantitative performance targets and prescribed methods of performance measurement for all aspects of building performance. Nevertheless, Clause 1.2.1.1.(1)(b) makes it clear that an effort must be made to demonstrate that an alternative solution will perform as well as a design that would satisfy the applicable acceptable solutions in Division B—not “well enough” but “as well as.”

In this sense, it is Division B that defines the boundaries between acceptable risks and the “unacceptable” risks referred to in the statements of the Code's objectives, i.e. the risk remaining once the applicable acceptable solutions in Division B have been implemented represents the residual level of risk deemed to be acceptable by the broad base of Canadians who have taken part in the consensus process used to develop the Code.

Level of Performance

Where Division B offers a choice between several possible designs, it is likely that these designs may not all provide exactly the same level of performance. Among a number of possible designs satisfying acceptable solutions in Division B, the design providing the lowest level of performance should generally be considered to establish the minimum acceptable level of performance to be used in evaluating alternative solutions for compliance with the Code.

Sometimes a single design will be used as an alternative solution to several sets of acceptable solutions in Division B. In this case, the level of performance required of the alternative solution should be at least equivalent to the overall level of performance established by all the applicable sets of acceptable solutions taken as a whole.

Each provision in Division B has been analyzed to determine what it is intended to achieve.The resultant intent statements clarify what undesirable results each provision seeks to preclude. These statements are not a legal component of the Code, but are advisory in nature, and can help Code users establish performance targets for alternative solutions. They are published as a separate electronic document entitled “Supplement to the NBC 2020: Intent Statements,” which is available on the NRC's website.

Areas of Performance

A subset of the acceptable solutions in Division B may establish criteria for particular types of designs (e.g. certain types of materials, components, assemblies, or systems). Often such subsets of acceptable solutions are all attributed to the same objective: OS1, Fire Safety, for example. In some cases, the designs that are normally used to satisfy this subset of acceptable solutions might also provide some benefits that could be related to some other objective: OP1, Fire Protection of the Building, for example. However, if none of the applicable acceptable solutions are linked to Objective OP1, it is not necessary that alternative solutions proposed to replace these acceptable solutions provide a similar benefit related to Fire Protection of the Building. In other words, the acceptable solutions in Division B establish acceptable levels of performance for compliance with the Code only in those areas defined by the objectives and functional statements attributed to the acceptable solutions.

Applicable Acceptable Solutions

In demonstrating that an alternative solution will perform as well as a design that would satisfy the applicable acceptable solutions in Division B, its evaluation should not be limited to comparison with the acceptable solutions to which an alternative is proposed. It is possible that acceptable solutions elsewhere in the Code also apply. The proposed alternative solution may be shown to perform as well as the most apparent acceptable solution which it is replacing but may not perform as well as other relevant acceptable solutions. For example, an innovative sheathing material may perform adequately as sheathing in a wall system that is braced by other means but may not perform adequately as sheathing in a wall system where the sheathing must provide the structural bracing. All applicable acceptable solutions should be taken into consideration in demonstrating the compliance of an alternative solution.”

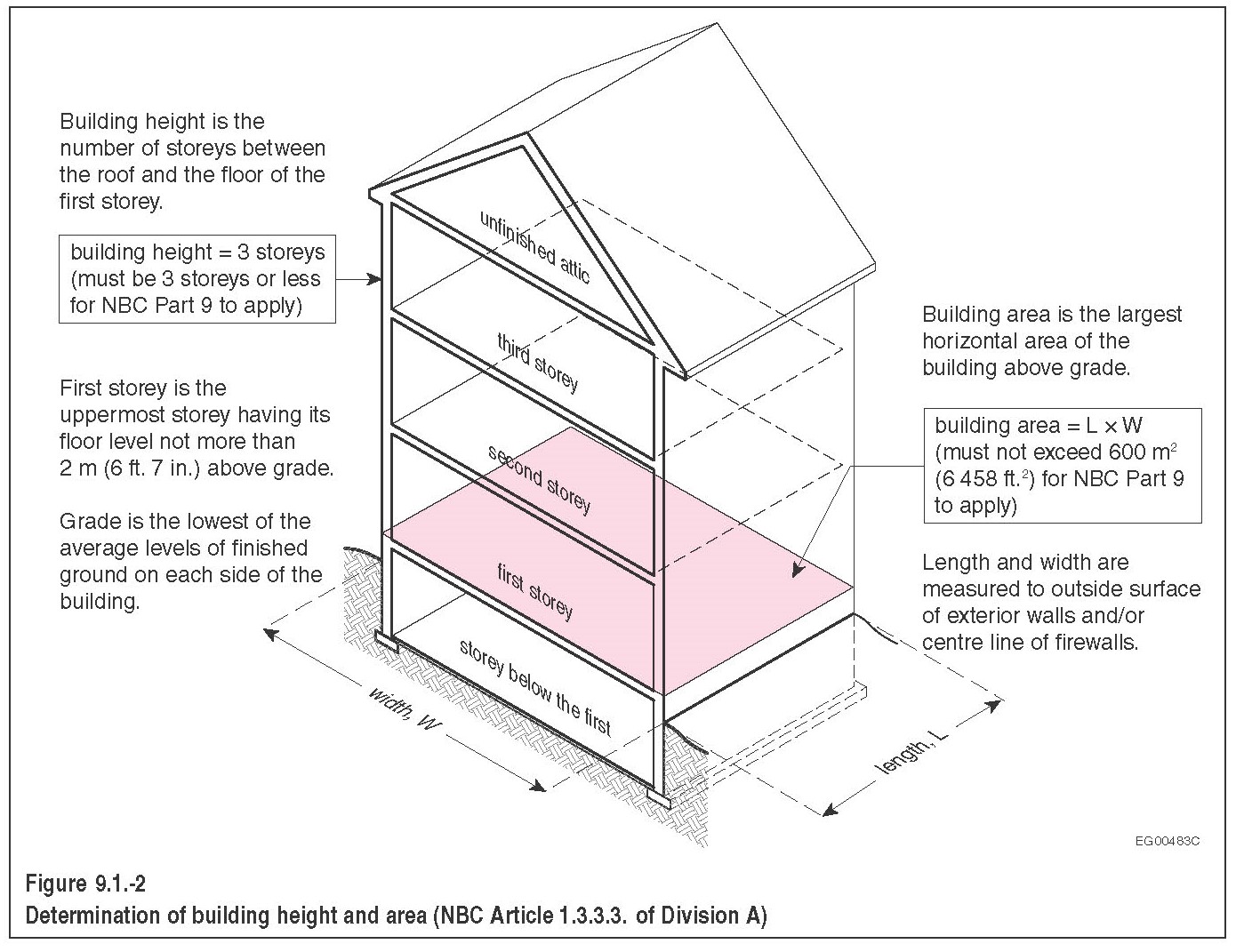

What is Part 9 of the building code and when can it be used?

From Divison A of the 2020 National Building Code of Canada:

1.3.3.3. Application of Part 9

1) Part 9 of Division B applies to all buildings described in Article 1.1.1.1. of 3 storeys or less in building height, having a building area not exceeding 600m2, and used for major occupancies classified as

a) Group B, Division 4, home-type care occupancies,

b) Group C, residential occupancies (see Note A-9.1.1.1.(1) ofDivision B),

c) Group D, business and personal services occupancies,

d) Group E, mercantile occupancies, or

e) Group F, Divisions 2 and 3, medium- and low-hazard industrial occupancies.

From Section 9.1 of the 2015 NBC Part 9 Illustrated User’s Guide:

“9.1.1.1. Application

This Article, by reference to NBC Subsection 1.3.3. of Division A, indicates that the application of NBC Part 9 is limited to buildings not exceeding a certain size that are used for certain occupancies. Buildings that are used for other occupancies or that exceed the specified size limits require special fire and structural safety features and are beyond the scope of the simplified requirements in NBC Part 9. Such buildings are regulated by the requirements in other Parts of the NBC. NBC Part 9 must be used in conjunction with NBC Parts 1, 2, 7 and 8, which apply to all buildings regardless of size or occupancy.

Many enforcement officials and designers refer to buildings within the scope of NBC Part 9 as “Part 9 buildings,” while those buildings regulated by other Parts of the NBC are generally referred to as “Part 3 buildings” or sometimes “Part 4 buildings.” However, the latter labels are misleading, since buildings that do not fall within the scope of NBC Part 9 must satisfy the requirements of all other Parts of the NBC, not just those in NBC Part 3 or 4.

NBC Part 9 is not only applicable to the design, construction and occupancy of new buildings, but is also applicable to the reconstruction, demolition, removal, relocation and occupancy of existing buildings (NBC Sentence 1.1.1.1.(1) of Division A). NBC Part 9 is most often applied to existing buildings when an owner plans to rehabilitate a building, change its use, or build an addition, or when an enforcement authority decrees that a building or a class of buildings must be altered for reasons of public safety. The degree to which requirements can be modified for application to an existing building without affecting the intended level of safety requires considerable judgement on the part of the designer and the authority having jurisdiction. New requirements are not intended to be applied retroactively to existing buildings that are not being modified.”

What is building area and how is it calculated?

From Division A of the 2020 National Building Code of Canada:

“Building area means the greatest horizontal area of a building above grade within the outside surface of exterior walls or within the outside surface of exterior walls and the centre line of firewalls.”From Page 25 of the 2015 NBC Part 9 Illustrated User’s Guide:

“Building area is the largest horizontal area of the building above grade.”

What is occupant load and how is it calculated for dwelling units?

From the 1995 NBC Part 3 Illustrated User’s Guide:

“Occupant load is the number of persons for which a building or part of a building is designed. The principal applications of occupant load are to determine the number and width of exit facilities that must be provided, the width of access routes leading to exits from within floor areas, the number of sanitary fixtures required in washrooms, whether a fire alarm system must be installed, and as one of the parameters used to establish whether a building is subject to the additional requirements for high buildings in Subsection 3.2.6.

Occupant load is determined on the basis of the total number of persons that the building, or a part of the building, is expected to accommodate. Temporary occupants of service spaces, including furnace rooms and electrical equipment rooms, and transient occupants of access corridors and washrooms, would not normally be counted in determining the occupant load, since any occupants of these latter areas would have already been included in the occupant load in the normally occupied parts of the building.”

Article 3.1.17.1. Occupant Load Determination of the 2020 National Building Code of Canada establishes that:

“The occupant load of a floor area or part of a floor area shall be based on... (b) 2 persons per sleeping room in a dwelling unit, or (c) the number of persons for which the area is designed, but not less than that determined from Table 3.1.17.1 for occupancies other than those described in Clauses (a) and (b), unless it can be shown that the area will be occupied by fewer persons.”

Additional References

Gates, B. & Sandori, P. (1984). “Fire Safety and the Design of Apartments.” Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. (Call Number CA1 MH 84F38)

https://assets.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/sf/project/archive/research/ca1_mh_84f38.pdf

Larden, A. et al. (1996). “Main Streets Development / Ontario Building Code (OBC) Study.”

https://www.codenews.ca/OBC/docs/OntarioMainStreets-A1995.pdf

Canadian Commission on Building and Fire Codes. (1998). “Recommended Documentation Requirements for Projects using Alternative Solutions in the Context of Objective-Based Codes (Discussion Paper).” Archived - National Model Construction Code document.

https://nrc.canada.ca/sites/default/files/2019-03/documentation_requirements.pdf

Bergeron, D. (2004). “Canada's objective-based codes“. 5th International Conference on Performance-Based Codes and Fire Safety Design Methods Luxembourg, October 6, 2004. NRC Publication Archive.

https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/accepted/?id=ad81d6f2-e76c-4eff-a428-de7e001d3527

“National Repository of Alternative Solutions: A national repository of alternative solutions previously accepted by local authorities, or by an individual province or territory, is being contemplated. Such a repository would make additional well-considered information available on-line, result in less "reinventing of the wheel," and speed up the evaluation of other alternative solutions. Proponents and authorities having jurisdiction could more easily investigate what has been accepted by other jurisdictions and under what limitations. However, there are many issues to be addressed before such a repository can become a reality: liability of the listing authority, obligation or pressure imposed on other authorities, disclosure of proprietary information, etc.”

Bergeron, D. (2006). “Training for objective-based codes in Canada“. 6th International Conference on Performance-Based Codes and Fire Safety Design Methods Tokyo, june 14-16, 2006. NRC Publication Archive.

https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/accepted/?id=97f4e41b-2850-47ab-8692-88eb4de7a2db

National Research Council Canada. Illustrated User’s Guide: NBC 2015 Part 9 of Division B: Housing and Small Buildings

https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=72431bc3-7a2e-4725-bdca-aace4b7f3837

Speckert, C. (2022). Jurisdictions: Maximum Permitted Height for Single Stair Buildings [Infographic]. McGill School of Architecture.

Retrieved from https://secondegress.ca/Jurisdictions

Public Architecture. (March 2023). Single Stair Residential Buildings. BC Housing Building Excellence Research & Education Grant.

https://research-library.bchousing.org/Home/ResearchItemDetails/8813

About Here. (December 11, 2023). “Why North America Can't Build Nice Apartments (because of one rule).”

Mendoza, E. & Smith, S. (March 2024). “Point Access Block Building Design: Options for Building More Single-Stair Apartment Buildings in North America.” Cityscape: A Journal of Policy Development and Research, vol. 26, no. 1, 431. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

https://www.huduser.gov/portal/periodicals/cityscape/vol26num1/ch25.pdf

Vancouver Urbanarium. (May 2024). “Decoding Density.”

https://urbanarium.org/decoding-density

LMDG Building Code Consultants. (June 2024). “Single Exit Stair: Ontario Building Code Feasibility Study.” Prepared for City of Toronto.

https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2024/ph/bgrd/backgroundfile-247234.pdf

Jensen Hughes Canada. (June 2024).”Single Egress Stair Building Designs: Policy and Technical Options Report, British Columbia.”

https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/farming-natural-resources-and-industry/construction-industry/building-codes-and-standards/reports/report_for_single_egress_stair_designs.pdf

Roman, J. (August 6, 2024). “Single Stair, Many Questions.” NFPA Journal.

https://www.nfpa.org/news-blogs-and-articles/nfpa-journal/2024/08/06/the-single-exit-stairwell-debate

About Here. (August 25, 2024). “Addressing the concerns around single stair apartments.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ozwkP9Zsi0Y

British Columbia Building Code. (August 27, 2024). “BCBC Revision 3 (PDF). Amendments to enable construction of single exit stair buildings in Ministerial Order BA 2024 03.”

https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/industry/construction-industry/building-codes-standards/bc-codes/errata-and-revisions

National Fire Protection Association. (September 2024). “Single Exit Stair Symposium Report.”

https://www.nfpa.org/en/forms/single-exit-stair-symposium-report

Boston Indicators & Utile. (October 2024). Legalizing Mid-Rise Single-Stair Housing in Massachusetts. Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies.

https://www.jchs.harvard.edu/research-areas/reports/legalizing-mid-rise-single-stair-housing-massachusetts

Jursnick, S. (December 2024). “The Seattle Special: A US City’s Unique Approach to Small Infill Lots.” Mercatus Center, George Mason University.

https://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/seattle-special-us-citys-unique-approach-small-infill-lots

Pew Trust. (February 27, 2025). “Small Single-Stairway Apartment Buildings Have Strong Safety Record.”

https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2025/02/small-single-stairway-apartment-buildings-have-strong-safety-record

City of Edmonton. (March, 2025). “Alternative Solutions Guide for Point Access Blocks.”

https://www.edmonton.ca/business_economy/new-commercial-building

This website, including all data and information incorporated herein, is being provided for information purposes only. For certainty, the author provides no representation or warranty regarding any use of or reliance upon the content of this website, including no representation or warranty that any architectural drawings comply with applicable laws including any applicable building code requirements or municipal by-laws. Any use of or reliance upon the content of this website by any person for any purpose shall be at such person’s sole risk and the author shall have no liability or responsibility for any such use of or reliance upon the content of this website by any person for any purpose. Prior to any use of or reliance upon the content of this website by any person for any purpose, consultation with a professional architect duly licensed in the applicable jurisdiction is strongly recommended.